Faith-inspired sustainability specialist Kamran Shezad and Chris Seekings consider the role religion can play in tackling climate change and environmental breakdown

Pope Francis wrote of climate change in his second encyclical: “To develop an ecology capable of remedying the damage we have done, no branch of the sciences and no form of wisdom can be left out, and that includes religion.”

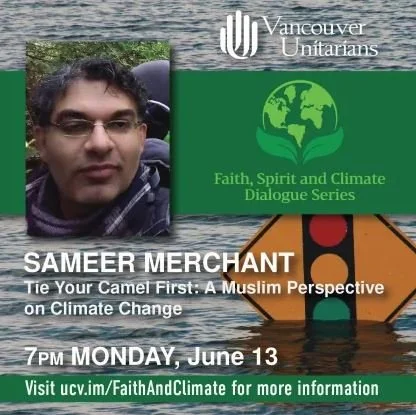

Prominent Islamic, Jewish, Buddhist, Sikh and Hindu figures have also attempted to instil a spiritual imperative into the environmental discussion. With 84% of the global population religious-affiliated, harnessing these groups may be one of our greatest tools in tackling the crisis. Kamran Shezad, sustainability advisor at nonprofit Muslim organisation the Bahu Trust, explains how people of faith are taking environmental inspiration from religious texts .

Divine power

“Faiths connect with people’s emotions and personal lives, so are an excellent method of mobilising people,” Shezad says. “In addition to values and teachings, faith institutions hold a huge amount of assets globally and have the power to drive enormous change.”

It is estimated that religious organisations control 50% of the world’s schools, 10% of financial institutions and 8% of the planet’s habitable land surface (source: Faith for Earth initiative). There are 37m churches, 3.6m mosques, and many thousands of synagogues and temples worldwide. “They own a huge amount of buildings, and so have to make decisions about how they use energy, water and distribute food,” Shezad explains. “They own half of all schools and educate a mass audience, and can lead by example on responsible land use.”

Moreover, faith institutions have an estimated $3trn invested around the world, with their purchasing power becoming increasingly apparent. The Church of England holds many millions of pounds in oil giants BP and Royal Dutch Shell, but is now one of numerous religious institutions supporting divestment from fossil fuel companies.

The moral high ground

Dr Fazlun Khalid is one of the most influential Islamic scholars on the environment, and founding director of the Islamic Foundation for Ecological and Environmental Sciences (IFEES). He drafted the Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change, which calls on all Muslims, “wherever they may be, to tackle the root causes of climate change, environmental degradation, and the loss of biodiversity”.

“As Dr Khalid puts it, ‘Islam is intrinsically environmental’, but that does not mean all Muslims are,” Shezad says. “For example, Saudi Arabia is the world’s second-largest producer of oil and one of the greatest contributors to carbon emissions and climate change.”

Only the US generates more oil, according to the country’s Energy Information Administration, and it is also home, ironically, to the world’s largest Christian population. “Environmental faith-based groups are overwhelmed by the dominant economic model in the US, while Saudi Arabia is dependent on a single resource,” Shezad says. “However, I think faith groups are beginning to reclaim the moral high ground.”

Currently, more than 43 faith-based organisations have accredited status with the UN’s Environment Assembly. These groups vary considerably in size, with some promoting initiatives in their local areas and others facilitating partnerships at national or international level.

The UK-based Faith for the Climate Network was launched in 2014 to encourage collaboration between faith communities and help boost their work on climate change. “Faiths acting together is a powerful witness to the wider world about our shared responsibility to care for creation,” says Lizzie Nelson, Faith for the Climate coordinator. “We know that the best way to engage people is not through fear, or telling people what they ‘ought’ to do, but by engaging with their core values and identity. This is how faith communities have such a key part to play in the wider climate movement.”

A common home

These partnerships mark a remarkable reversal of the tensions witnessed between competing religions throughout history, with the environment firmly at the heart of this paradigm shift.

As part of The Time Is Now’s campaign on climate change, a mass lobby of the UK parliament was recently attended by the former Archbishop of Canterbury Lord Rowan Williams, chair of the Mosques and Imams National Advisory board (MINAB) Qari Asim MBE, Rabbi Jonathan Wittenberg of the New North London Synagogue, Vishvapani Blomfield of the Triratna Buddhist Order, and Prubhjyot Singh from EcoSikh.

“So many narratives in the media around faith are negative, focusing on abuse, conflict or religious extremism,” says Nelson. “But faith inspires people to act and work together for the common good.”

On a global level, the Faith for Earth initiative was launched by UN Environment in November 2017, with three main goals: to inspire faith groups to advocate for the environment, to make faith organisations’ investments and assets green, and to connect faith leaders with decision-makers and the public.

“Coming together for climate action is a practical example of what people of faith are already doing day-to-day for the planet, and a vision of how we want the world to be,” adds Nelson.

“The best way to engage people is not through fear, but by engaging with their core values”

Love thy neighbour

Footsteps – Faiths for a Low Carbon Future is a local grassroots organisation in Birmingham, bringing together various faiths to ensure the city is carbon neutral by 2030. It is also involved in the Brum Breathes campaign for cleaner air. “The impact is already showing great signs of its effectiveness,” says Footsteps chair Ruth Tetlow. “The ‘Golden Rule’ is a shared ethic across all faiths.”

Meanwhile, 18 of the Bahu Trust’s 22 mosques have installed solar panels and converted to renewable energy. Educational sermons have been developed, plastic-free events organised and community clean-ups of local streets carried out. This year, it published a joint statement with the IFEES and the MINAB urging all Muslims to divest from fossil fuels and switch to renewable energy. “The Bahu Trust will now work with IFEES and MINAB to develop an educational programme for Muslim communities on how to ensure they are not invested in the fossil fuel industry,” says Shezad.

More examples include EcoSikh, which will this year plant 550 fruit trees along canals in England’s West Midlands to commemorate the 550th birthday of the Sikh religion’s founder Guru Nanak. And Christian Climate Action – inspired by Extinction Rebellion and religious teachings – has been carrying out acts of non-violent direct action demanding change. “Faiths have a long tradition of expecting their followers to take self-denying actions to care for the earth and those suffering,” Tetlow adds.

A call to action

Dr Iyad Abumoghli of UN Environment and founder of the Faith For Earth initiative is working to develop a formal coalition to strengthen engagement between religious leaders and help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The coalition would be composed of a ‘Council of the Elders’, bringing together high-level faith leaders such as the Pope and Grand Imam of al-Azhar, while a 'Council of the Youth' would mobilise young faith leaders from every continent to act as global ambassadors.

“Collaboration is Goal 17 of the SDGs,” says Jeffrey Newman, Rabbi Emeritus of the Finchley Reform Synagogue. “There is more that we share together than divides us, and we are now faced with the greatest potential calamity for life on Earth.”

CEOs of faith groups will also form part of the coalition, while a faith-science consortium of theologians, scientists and environmentalists will connect faith teachings to caring for natural resources.

“People argue that religion is incompatible with science and that they conflict with each other – I don’t buy that argument,” Shezad says. “Many of the greatest scientists of our time have been inspired by their faith and science. I would say that religious texts are complementary to science, and provide solutions to safeguarding the planet.”

Faith groups are also preparing for further international collaboration at next year’s COP 26 climate summit in Glasgow. “Faith for the Climate is beginning to gear up and make early preparations so that the network can efficiently lead its member organisations and ensure the faith presence is effective,” Shezad adds.

“Many of the greatest scientists of our time have been inspired by their faith”

One for all

Although the escalating climate crisis has helped bring groups together more than ever, collaboration between faiths is not that new. In 1986, Prince Philip – then president of WWF International – invited leaders of the world’s five major religions to discuss how faiths can help protect the natural world. Organisations like the IFEES and Alliance of Religions and Conservation have been active ever since.

The problem is that this has not translated into meaningful enough action among the upper echelons of society, particularly in the West.

“In a lot of Western countries, politicians do not make the connection between environmental protection and religious texts,” says Gopal Patel, director of the Bhumi Project, a Hindu environmental group. “Political leaders from the Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh and Jain backgrounds probably do make that connection more, but how much they care about protection of the environment compared to economic growth, now that’s another question. All sectors of society need to work to address the crisis.”

Although she does not practice a particular religion, conservationist Jane Goodall has spoken of a “great spiritual power” that she feels when out in nature, and this year called on all faith-based organisations to join the climate movement.

“The practical work on sustainability and protecting the environment is universal and does not require a faith belief,” Shezad explains. “In a conversation with Dr Khalid, a secular person questioned whether a ‘God’ would subject this planet to climate change. Dr Fazlun responded by saying: ‘Welcome aboard, let’s save the planet first and we can then argue about God.’”

This piece was originally published on Transform on December 13 2019.