After two years of COVID-19-restricted access to the holy sites in Mecca, one million Muslims are expected to arrive as they respond to the call of hajj this year. Fundamentally, the hajj is embedded in a journey and an encounter.

Outwardly, it is an enactment tracing the footsteps of Prophet Ibrahim (a significant figure among all three Abrahamic faiths). Inwardly, it is a spiritual journey to conquer the self and to dampen the temptations of ego with the purpose to recalibrate our place in the cosmos and examine our priorities in this world. The two are intricately woven into one through the concept of the haram.

Haram literally means: to put restrictions or limitations on something — and is commonly used to imply the forbidding of certain actions to protect that which is sacred. For the pilgrim, entering this sacred state is signified by the donning of simple clothes that are meant to remove all societal representations of wealth or social differences.

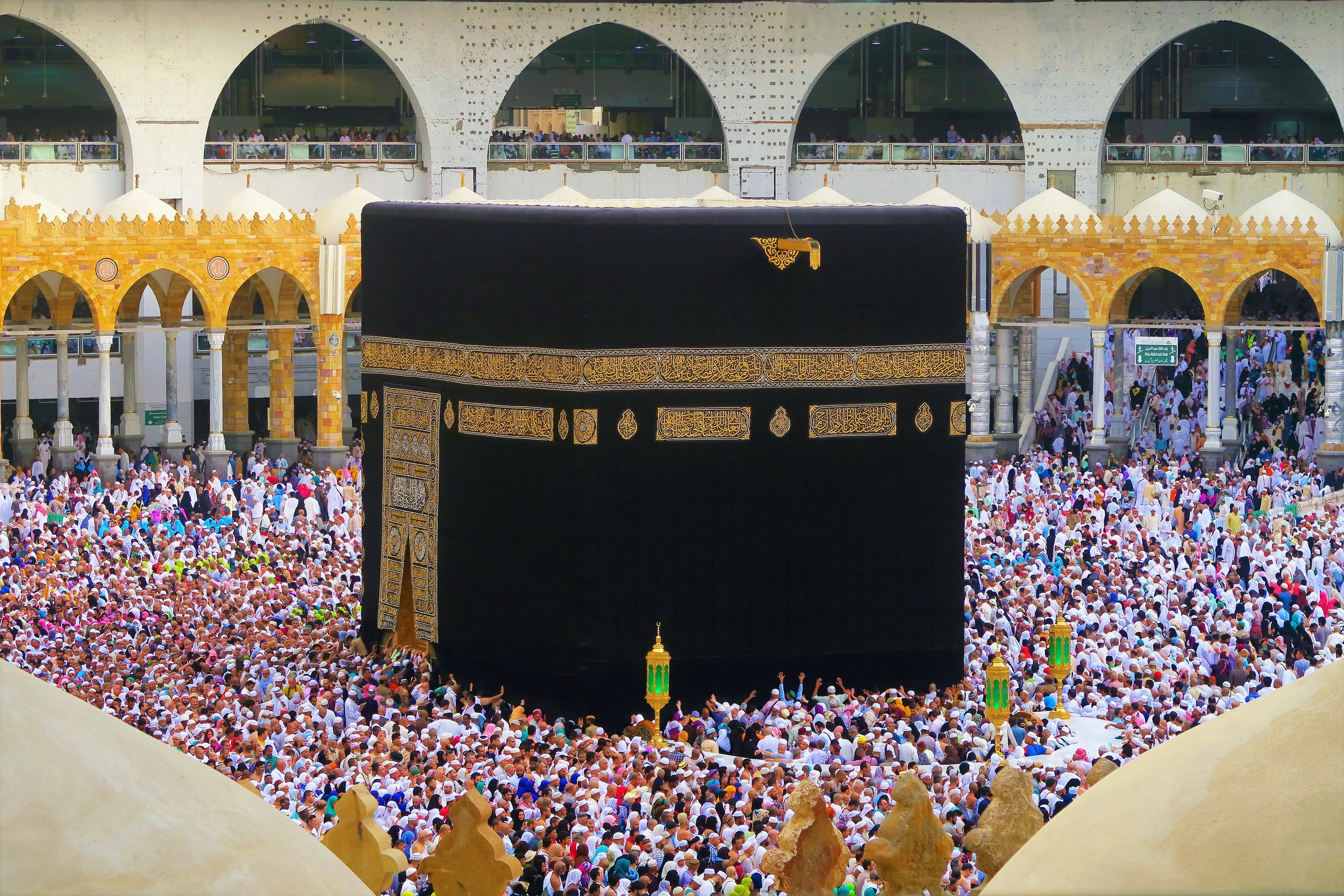

Rituals of hajj are meant to tame the ego and seek a state of harmony with the surroundings. Indeed, haram is further expressed in the context of time and space. The three months of hajj are known as the sacred months. Haram also extends to the geographical area that surrounds the Kaaba in the precincts of Mecca, a space restored as a sanctuary since 628 CE. Arguably, this makes the Kaaba one of earth’s earliest protected sanctuaries, bestowing a sacredness to the place, which can be extended to the planet and the cosmos.

As humanity is reaching an epiphany in the trajectory of climate change on the planet, hajj is inviting us to explore and embrace new frameworks to address this existential threat and ground environmental action and policies in different paradigms.

Ashlee Cunsolo, a leading voice on climate change and human well-being, said “climate change is asking us to be different” and “to accept the honest truth.” But as philosopher Kwame Appiah observed, humanity’s moral failings are defined less by lack of knowledge and more by pursuing strategic ignorance by invoking tradition, or necessity, in order to avoid facing those inconvenient truths. So, reversing current trajectories will require more than science and data, but action anchored on moral and ethical paradigms to restore our broken relationship with the planet.

Firstly, the environmental protection laws must be built on a different calculus based on an inclusive legal protection framework that is extended to animals, plants, oceans, water reservoirs and land. This must aim to halt the loss of biodiversity, which has been declining sharply. The world has seen an average 68 per cent drop in mammal, bird, fish, reptile, and amphibian populations since 1970.

Secondly, we need to find a path to moderation and reverse the consumption trends of the past 100 to 150 years. These consumption patterns and human activities are altering the planet ecosystems on a geological scale. Transitioning to a net-zero world calls for a complete transformation of how we produce, consume and move around.

If we fail to reverse current trajectories, the impact of climate change on humanity will be unimaginable. For example, it is predicted that up to 250 million people will be displaced by the 2050 as a result of extreme weather conditions, dwindling water reserves and a degradation of agricultural land.

It is time for humanity to build hope by infusing different world views in the circle to address a crisis that is impacting all of creation. Hajj uniquely presents an intersectionality between religion and the environment, as it offers us a rich discourse to engage in environmental protection on a higher moral pedestal: the sacredness of the universe and individual responsibility.

Abdul Nakua, an executive with the Muslim Association of Canada, serves on the board of directors for Ontario Nonprofit Network and is a member of the Nonprofit Sector Equitable Recovery Collective.Memona Hossain, a Ph.D. candidate in ecopsychology, is an environmentalist and has served on the board of directors for the Muslim Association of Canada.

This piece was originally published in the Toronto Star on July 8, 2022.